Read the review and find out why the Professor thinks the answer is a resounding yes.

[Prof’s Note: With the iconic XI dropping in two luscious colorways over the past five days (see Hypebeast for sweet pics of the latest drops), I felt compelled to bring back my review of this most loved shoe. Note that this review was originally published in December of 2001.]

There have been 15 shoes in the Air Jordan line to date and several have been, not only memorable, but historic. The Air Jordan I, Air Jordan V, and Air Jordan VI will likely be remembered as seminal works in the history of athletic shoe design. But of all of the Jordans released thus far, one best captures the essence of the man and his game: the Air Jordan XI.

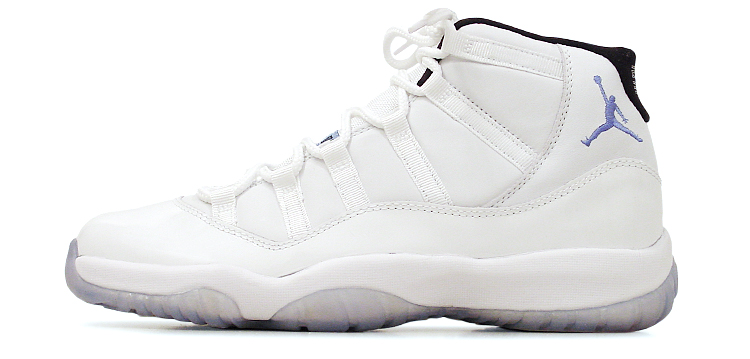

figure 1. The Air Jordan XI in its most iconic White/Black–Dark Concord colorway. Sneaker fans have come to love its trademark patent leather rand, but try to imagine how shocking the XI would have been when it first hit store shelves in 1995.

The Nike Air Jordan XI was first released for the 1995–96 NBA season, Michael’s first full season back in the NBA after his two year retirement. At that point, some began to feel that the Air Jordan line had lost its way after a series of shoes—specifically the VII, VIII and IX—that didn’t quite live up to the level set by the magnificent Air Jordan VI. And then there was the X, which many sneakerheads of the era felt was the weakest release in the history of the Air Jordan line to that point. But with Michael rejuvenated and primed to reclaim his position atop the NBA, Nike stepped up in a big way and provided His Airness with a shoe that surpassed all that had come before it.

figure 2. Here’s the Air Jordan XI in its wickedly clean White/Columbia Blue–Black colorway. Note the use of synthetic leather in place of the ballistic nylon mesh employed on the upper of the White/Black–Dark Concord colorway pictured at top.

While the Air Jordan XI made use of some design elements previously incorporated into the Jordan line—elements like a translucent rubber outsole and a speed lacing system—on the whole, the shoe was strikingly new, and a clear representation of Michael’s distinctive sense of style. The design cue that stands out most, of course, is the XI’s patent leather rand, which extends over the toebox and wraps completely around the upper. To my knowledge, no other athletic shoe had made use of patent leather prior to the XI.

figure 3. And here’s the Air Jordan XI in Medium Grey/White–Cool Grey, which debuted as a retro release in 2001. If there’s such a thing as a low-key colorway of the Air Jordan XI, this is it.

And, more than just a showy design element, the robust patent leather serves as a reinforcing structure, boosting the shoe’s lateral support. The patent leather can’t quite match the level of support afforded by modern-day shoes that wrap Phylon (an example being the Nike Air Big Flyer Force) or TPU (an example being the Nike Air Pippen IV) high up around the midfoot and heel, but support levels are better than you’d expect from a shoe with a relatively minimal, largely-textile based upper. And there’s no question that the use of patent leather makes the XI a shoe that attracts attention—though, whether this is a positive or a negative will depend on your own appetite for bling.

As alluded to above, the patent leather rand buttresses a base of ballistic nylon mesh (note that some colorways feature synthetic leather in place of the nylon mesh). The upside of this extensive use of mesh is that the Jordan XI is a very light, comfortable shoe. The only downside is that, because the nylon mesh is highly pliable, ankle support is not quite what it could be. Thanks to the high cut of the lacing system it’s still better than average, but an anti-inversion structure would have made it excellent.

figure 4. Visible here is the Air Jordan XI’s translucent rubber outsole and its innovative full-length carbon fiber “spring plate,” which helps boost support and responsiveness underfoot. This shot also highlights the shoe’s speed lacing system, which does indeed help to speed the process of getting the shoe on and off. Just make sure to pull the laces tightly if you want to maximize fit and support—particularly on colorways that feature the more minimal ballistic mesh-based upper.

Contributing to the overall support and stability of the Air Jordan XI is its full-length carbon fiber “spring plate”. I believe that Nike refers to this device as a spring plate because the rigidity of its carbon fiber construction causes the plate to quite literally spring back to its flat state after the forefoot is flexed, potentially returning some of the energy that went into flexing the shoe back to the wearer. I can’t say that I necessarily noticed any added spring to my step, but the XI did feel highly responsive and offered excellent support and stability underfoot. The only potential downside that I could see to the extended plate is that lighter players may find the forefoot of the shoe to be overly stiff and clunky. Take a few jab steps when trying on the XI to gauge your comfort level with its rigidity up front.

figure 5. Pictured here is the Air Jordan XI in Black/Varsity Royal–White, which is colloquially referred to as the “Space Jam” colorway, a reference to the 1996 live-action/animated film of the same name starring MJ and Bugs Bunny. Note that the XI’s traction is unusually good for a shoe that features a mostly translucent rubber outsole. Note also that the translucent portions of the outsole will yellow, especially if left exposed to heat or sunlight.

Another component that almost certain contributes to the XI’s responsive feel underfoot is its full-length Air-Sole unit, which does a great job providing cushioning at both the forefoot and heel. I was actually somewhat surprised by the level of cushioning that the shoe provided. In fact, it may actually be a bit too soft for bigger/heavier players, but I think most guards and small forward-types will love it.

One last aspect of the shoe that surprised me was its traction. I’ve been disappointed in the past by the traction, or lack thereof, of previous Air Jordan models featuring translucent outsoles—e.g. the Air Jordan V and VI—so I was happily surprised to find that the Air Jordan XI provides very good on-court grip. I can, however, report that one negative characteristic of translucent soled Jordans is indeed carried over to the XI: yellowing. Keeping the shoe out of sunlight and away from heat sources should slow the process, but this would be rather impractical if you actually intend to wear the shoes.

figure 6. Here’s a bonus pic to help keep you warm through these frosty winter months: The Air Jordan XI in Black/True Red–White. As the kids might say, “It’s straight fire!”

To sum up, the Air Jordan XI Retro—more so than any other Jordan Retro to date—delivers the goods, not only in terms of style, but also substance. The XI is a shoe that you could actually play a full game in without feeling like you’re compromising your own performance or taking years off the usable life of your joints (read my review of the Air Jordan VI Retro for a counter example). Some may feel that the shoe’s iconic patent leather rand makes it a bit too, er, distinctive, to wear in public. But others will love it precisely for its in-your-face ostentatiousness. Whatever you think of its appearance, the Air Jordan XI Retro is a great choice for guards and small forwards who value comfort and light weight, and seek a shoe that offers an optimal blend of cushioning and response underfoot.

Who’s Worn It

Michael Jordan (G- Chicago Bulls); plus, several players, including Reggie Miller (G- Indiana Pacers) and Toni Kukoc (F- Philadelphia 76ers), have worn the Air Jordan XI this pre-season